The Evolution of Active-sport-event Travel Careers Reviewers Critique

Assessing and Considering the Wider Impacts of Sport-Tourism Events: A Research Agenda Review of Sustainability and Strategic Planning Elements

1

University of Rijeka, Faculty of Tourism and Hospitality Management, Primorska 42, 51410 Opatija, Croatia

2

Liverpool Business School, Liverpool John Moores University, 4/6 Rodney Street, Liverpool L1 2TZ, Britain

*

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

Received: vii May 2020 / Revised: 22 May 2020 / Accustomed: 27 May 2020 / Published: i June 2020

Abstruse

Sport-tourism events create a wide spectrum of impacts on and for host communities. However, sustainable sport-tourism events, which emphasize positive impacts, and minimize negative impacts, practise not arise by risk—they demand conscientious planning and implementation. This newspaper aims to review and systematize a broad spectrum of social impacts that outdoor sport-tourism events create from the perspective of key stakeholders and addresses strategic planning elements necessary for achieving event sustainability. To achieve its objectives, the authors examined the Spider web of Scientific discipline Core Collection (WoSCC) database, searching for relevant scientific papers focusing primarily on the impacts and legacy of sport events, strategic planning elements, and attributes necessary for achieving sustainability through a systematic quantitative review and content analysis. The results indicate that the relevant literature mostly focuses on economical impacts, followed by social and ecology impacts. Well-nigh studies focus on Europe and Asia, with the Olympic Games and FIFA World Cups being the most popular blazon of event studied. To systemize event and destination strategic elements and attributes for achieving sustainability, this study considers eight categories: social, cultural, organizational, logistic, communication, economical, tourism, and environmental. This paper identifies the main research gaps, proposes a new holistic sport-tourism events enquiry agenda and provides recommendations then that organizers can avert planning, organizing, financing mistakes and improve leverage future sporting events.

1. Introduction

Over the by few decades, event tourism (culture, sporting and business organisation-related events) has become a quickly expanding segment of the leisure travel market [i,two,3]. The connection between sport and tourism is non new, and scholars accept considered the rise of sporting events as one of the most meaning components of event tourism and one of the most extensive elements of sporting tourism [iv,5]. The growing utilise of sporting events is an endeavour to expand economic development opportunities and reach tourism growth [half dozen].

Management and planning issues are a key focus [7,8] and researchers are interested in the impacts events have on the host customs [nine]. Therefore, the impacts of sporting events on destination are many. The triple bottom line (TBL) is arguably the nearly widely accepted approach to identifying and measuring impacts [10], which is an assessment of economic, socio-cultural and environmental influences as pertinent to sporting events and sport tourism on the local communities [11,12,xiii,fourteen,15].

Economic and related tourism benefits are seen as tangible or 'hard' impacts, and thus local stakeholders see the hosting of events every bit beneficial. Economic benefits include target investments in sport and event infrastructures, employment, prolonged tourism season, increased tourism, and new taxation revenues [xvi,17,xviii,19,20,21]. Economic benefits too include some non-monetary effects, such every bit generating media attention and destination image enhancement [22,23,24,25,26,27]. 1 betoken of concern is the high (and sometimes excessive) costs and spending involved with building and preparing infrastructures, and this can result in increased taxes, higher prices and housing costs locally [28,29].

Social/cultural impacts are often considered 'soft' impacts [thirty,31], and scholars view the assessment, measurement and management of these impacts as more difficult [two,32]. Among these intangible impacts is a focus on local resident quality of life, enhanced social cohesion and pride in place, a new perceived destination epitome, and the potential to increase sport participation amid locals [33,34,35,36]. However, a concern is that an increase in tourism can result in cultural conflicts amid residents and tourists, traffic congestion problems, security and criminal offense concerns, too every bit vandalism—these are seen as negative impacts among local stakeholders observed in recent research [28,37,38].

Environmental impacts are also an important simply challenging area of focus among scholars today. Some findings suggest that positive environmental impacts upshot when new sport infrastructures are congenital on devastated or reclaimed land and are a strategy to better a site (see [39,40]), merely in about cases local stakeholders perceive environmental impacts negatively. Without advisable regulations and careful planning, new sports tourism infrastructure can pb to environmental consequences in a given area [28] and with high concentrations of people attending events, mass gatherings of event-goers see increases in waste, air and water pollution, also equally higher racket levels [28,29,41].

Although the primary dimensions of sport event impacts are established (i.e., economic, socio-cultural and environmental), the scope of these dimensions are not unified—and sometimes event in very different touch on outcomes. What is also noticed is that particular impacts could belong to different dimensions. Furthermore, some impacts are mentioned more oftentimes than others, leading to a conclusion that not all type of impacts are equally of import, or at least not equally assessed. This makes this area of research open to further scrutiny and systematization. In addition, different stakeholders (e.thousand., organizers and managers, sponsors, spectators, active participants or locals) can accept very different perspectives and impressions of an touch. Thus, an touch depends on many factors (type of the upshot, blazon of sport, demographics of the host community), but an accepted conclusion amid researchers is that larger events outcome in greater impact, and these impacts can be positive and negative. In case of large-scale events, the impacts could spill over to non-host peripheral communities [forty].

A claiming that researchers demand to consider is that because each stakeholder group is involved differently in an event, they each take unlike expectations from an event, and thus value the importance of particular impacts of the event quite differently. While the event organizers and managers are actively involved in the outcome organization, the local population tin can too exist actively (e.g., past volunteering or spectating) or passively involved into the issue. However, because the fact that locals live in the host destination, an upshot held in shut geographical proximity will directly bear on local residents. Their back up plays an of import role in making decisions about hosting and organizing the sporting result, the success of the upshot and further tourism development in the destination. It is therefore necessary to have a wide support and participation of the local community to ensure a long-term growth [42]. However, the extent of local resident support will depend on a residuum between perceived benefits and costs of the event [forty]. A critical point to consider is that non all members of the hosting community, such as local residents, local business organizations or financial institutions (meet [43]) have an equal (positive or negative) perceptions of the impacts that the event they will host volition have on their local customs [44,45].

In general, event organizers desire events to be sustainable, meaning that events will produce (in each dimension) more social benefits than costs to the overall community. It means that they seek, in collaboration with other stakeholders, to ensure financial viability and maximize other positive impacts, while eliminating or minimizing the negative ones in social club to respect and appreciate the interests of all those directly or indirectly involved and interested in the effect itself. This certainly does not happen by chance, and sporting events need careful planning and implementation. In the planning stage, it is important to define specific (strategic) elements. This means defining consequence and destination attributes that will be a mandatory content to include when planning and preparing the event (due east.m., ecological public traffic, recycling program, offering of local products, cultural program, employment of local population, consequence legacy), so that aspects can stay permanent over a prolonged menses of time [6,46].

Consequently, in order to direct events on positive results and sustainability, for both the organizers and for the local population, it is necessary to focus on strategic elements necessary for efficient and effective event planning and arrangement. Indeed, controlling, participation in events and loyalty to an event very often depend on satisfaction with diverse event elements/attributes in improver to entertainment, attractions, and supplemental destination activities [47,48,49,50,51]. Event practitioners have created a several important guides linking the need for sustainability principles within sporting event organization, including the Aureate Framework [52]. While these guides provide just a framework, previous research has failed to report the relationship between specific strategic event and destination elements or attributes on i side, and event impacts on the other. If a relationship between a item strategic element and a specific event impact exists, i can presume that putting more accent on that element during the planning phase will positively contribute to the realization of the related impact. In other words, there is footling explanation of what strategic planning deportment are necessary to undertake to produce specific positive impacts. This is specially the case with the staging of outdoor sporting events, which are more sensitive in ecological terms (run across [53]).

This paper will address the wider impacts of sport-tourism events equally well as strategic planning elements for achieving outdoor sport-tourism events' sustainability based on a systematic literature review of published journal articles. More precisely, it will review the published literature in order to systematize a wide spectrum of social impacts that outdoor sporting events create from the perspective of key stakeholders, besides as the strategic planning elements necessary for achieving sustainability. To accomplish this, we define the post-obit research questions:

-

RQ1: What is most commonly mentioned impact in sporting events relevant literature?

-

RQ2: What types of sporting events are studied the most?

-

RQ3: What strategic planning elements are necessary for achieving sustainability, based on what the literature assessed mentions as the most of import?

This paper continues with a description of the methods used to behave this systematic literature review before presenting the findings. The discussion and conclusion highlight cardinal results to identify directions for future sport-event tourism studies.

2. Methodology

A systematic literature review method has often been practical to ameliorate understand diverse kinds of topics on sports tourism and sustainability-related research directions [54,55]. In addition, examining databases is an appropriate approach to exploring the extant of literature on the focus areas. The chosen database for this enquiry was the Web of Science Core Collection (WoSCC) considering this database includes top-rated peer-reviewed journals with international scope and coverage. While there are several complementary approaches to contribute a formal and systematic literature review [55,56,57,58,59,lx,61,62,63], given that the study of sporting event organisation and impacts is indeed heterogenic and involves multiple disciplines, methodological approaches and topics, this study used a 2-phase process.

2.1. Phase i

In conducting the review of impacts that sporting events create and referring to research question RQ1 and RQ2, we practical a systematic quantitative literature review. This answers one or more research questions, selects criteria for the inclusion/exclusion of the studies, requires a preliminary overview of the current state of research, helps identifying research gaps and proposes future inquiry agenda [55,56,62]. This detail study used a structured method to address detail research questions, thus aiming for methodological transparency and reliability, likewise as systematic and comprehensive search on a specified topic. Moreover, we used a quasi-statistical approach in gild to categorize, quantify, and identify trends in research over determined timeframes.

A comprehensive review was conducted from November 2019 to January 2020, thoroughly searching the WoSCC database for scientific journal papers published in the English language that contain the terms 'sport tourism event' and 'touch' in the topic (from titles, abstracts or keywords) from early publishing dates to the end of Dec 2019. While being aware of conceptual differences between the terms "outcome impacts" and "effect legacies" [62,64], these two terms are often used interchangeably, and we therefore decided to search for both terms separately. Hence, another review was conducted in parallel, thoroughly searching WoSCC database for scientific journal papers published in the English language language that contain the terms 'sport tourism event' and 'legacy'. These searches revealed 296 papers written in English language language, from which 220 on "event impacts" enquiry and 76 on "consequence legacies" inquiry in the WoSCC database. However, an initial assay of selected papers revealed that many of the identified publications were non enquiry papers and/or dealt with the sporting event impact and legacy concept in an unsubstantial way. Based on the exclusion criteria, the concluding sample contains in total 77 papers.

When reviewing the final sample, the authors defined several categories (eastward.g., type of event, country, type of impact, blazon of element/attribute) by which to sort and quantify the data. Direct extraction helped classify data into categories, thus assuasive new findings to emerge (see [62]). The kickoff author stored, coded and categorized data manually and and then counted frequency of appearance within particular categories. The first writer shared preliminary results with the other two authors, and then all three authors jointly evaluated and agreed on the results.

two.two. Phase 2

When it comes to RQ3, that is, papers focused on strategic planning elements/attributes necessary for achieving sustainable events, we repeated a similar process as in Stage 1. The WoSCC database was first searched for scientific periodical papers in English language that comprise the terms 'sport', 'tourism', 'consequence' and 'element' in the topic (from titles, abstracts or keywords) also from early publishing dates to the end of December 2019. In parallel, the WoSCC database was searched for scientific journal papers in the English language that contain the terms 'sport', 'tourism', 'upshot' and 'chemical element' or 'aspect' in the topic inside the aforementioned flow. At that place were considerably fewer papers and the two samples contained 33 papers in the enquiry of 'sport, tourism, event, element' and 34 papers in the research of 'sport, tourism, consequence, aspect'. Among the publications, there were papers that referred to outcome and destination elements/attributes every bit determinants of tourists' satisfaction, experience, or revisit intention, and we excluded these publications from the analysis. Simply a few of them referred to event and destination elements and/or attributes in relation to events' impacts and sustainability. Seven papers referred to strategic upshot and destination elements, and merely 10 referred to strategic event and destination attributes, making a concluding sample of 17 papers.

For more than profound insight into the focal papers, authors applied content analysis. Content analysis allows researchers to analyze text systematically and to notice underlying concepts and hidden qualities and relationships betwixt concepts [55]. The first writer stored and categorized data manually regarding whether they are consequence or destination elements/attributes. Then, the inductive interpretation method (i.e., inductive coding) was useful to allocate data into meaningful planning and organizational dimensions (see [62]). Therefore, the coded dimensions were derived straight from the text data. The start writer shared their preliminary results with the other 2 authors, and then all three authors jointly evaluated and agreed on the results.

3. Results

iii.one. Results of the Stage i

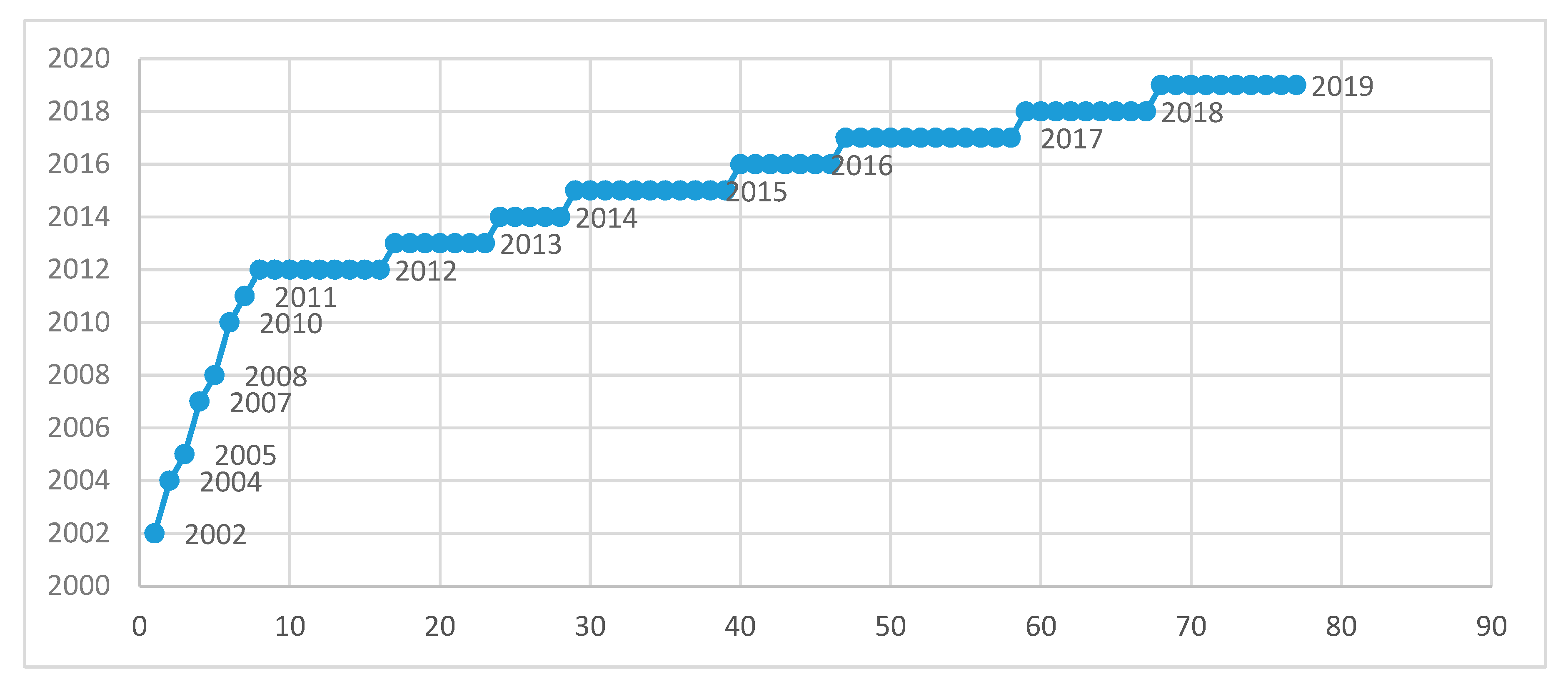

The first research on events impacts and legacy contained 77 scientific papers written in the English language language and all published in the 21st century (demonstrated in Effigy 1). Fewer papers appear from 2002 to 2011, with increases shown from 2012 to 2019.

As displayed in Table 1 the journals with the nigh papers include Sustainability (eight publications) and Tourism Management (seven publications), followed by European Sport Management Quarterly (vi publications) and Journal of Sport Management (five publications). It is evident, from the results, that these journals belong to the domains of sport, tourism, events, and sustainability.

Amidst them, 60 research papers were empirical, fifteen theoretical (literature reviews) and two included both theoretical and empirical enquiry. There were a number of empirical studies conducted inside unlike sports and sport events contexts. Most researched events were the Olympic Games: Summertime Olympic Games (ten publications), Winter Olympic Games (8 publications) and Paralympic Games (1 publication). World cups were also a common result focus, FIFA Globe Cups in item with ten publications and other international and national races. Furthermore, most studies were focused on football game or soccer (13 publications), wheel racing (iv publications), running races, athletics, golf and Formula one (two publications), and rugby, skating, swimming and surfing with only one publication. The rest relate to multi-sport events similar the Olympic Games (18 publications). In empirical research studies, the authors nerveless information from cardinal stakeholders (including, local residents, organizers, and participants), using surveys or interviews.

Every bit shown in Table 2, the review reveals that the continent where the bigger number of studies were conducted is Europe (19 publications), followed by Asia (16 publications). A smaller number of studies were conducted in Africa (nine publications), generally in the catamenia of FIFA World Cups, and Due north and Southward America (eight and five publications, respectively). Apropos Australia, in that location were two studies. 3 studies were conducted on different continents at the aforementioned time [65,66,67], with 15 conducted as a review of the existing literature without addressing any location.

Table 3 displays the different countries most commonly studied. In the first row, South Africa and Korea (five publications), following with Prc, Croatia and USA (four publications) and Brazil and United kingdom (iii publications). Canada, Hellenic republic, Japan, Portugal were as well inquiry locations (two publications). There were four studies conducted in different countries at the aforementioned fourth dimension [17,65,66,67]. Studies included in this newspaper testify enquiry conducted in more than 22 other nations across all inhabited continents.

As mentioned in the introduction, the organisation and implementation of sport-tourism events create different economic, socio-cultural and environmental impacts on the local community (both positively and negatively). Tabular array 4 systematizes the frequency of the main affect dimensions (economic, social and ecology impacts) and sub-dimensions from the research sample, equally well as their categorization as existence positive or negative impacts on/for the local community. But to note, each paper normally referred to more than than one impact (sub)dimension; so, this explains why the total sum of all (sub)dimensions is higher than the number of analyzed empirical research papers (threescore + 2 = 62 papers).

Scholars apply economical touch studies to a wide range of sporting and recreational events, which authors increasingly view them as an economical development tool (in addition to the achieving of recreation benefits). As displayed in Tabular array 4, this enquiry confirms the claim of previous studies that economic impacts are often more than researched and the non-economic outcomes, particularly environmental, are frequently overshadowed [42,68]. The results bespeak 81 positive and xx negative dimensions of economic impacts of sport-tourism events, 37 positive and nine negative dimensions of socio-cultural impacts, and 21 positive and eleven negative dimensions of environmental impacts.

The positive economical impacts of sport-tourism events generally focused on fostering tourism evolution, such as increased tourism revenues, development of tourism resources and infrastructure and tourism promotion. The results relate to other economic benefits such as the enhancement of destination/land image, increased investments, public infrastructure improvement, increased business and export opportunities for local companies, new job opportunities, and economic sustainability. Negative economical impacts mostly refer to the local population: higher living costs, college prices of housing, goods and other local services, not-refundable investments with incorrect use of public funds, or lack of strategic planning. Positive socio-cultural impacts focused on community benefits, such as social sustainability contribution to residents lives, socio-cultural heritage and uppercase development, increased socio-cultural substitution, increased interest in sports and events, increased participation in sport/physical activity, community-oriented regeneration, appointment in social, cultural and educational issue leverage, preservation of local traditions, and political and psychological benefits (due east.yard., increased pride and community spirit). The nearly oft negative cited socio-cultural impacts were crime and vandalism, terrorism, cultural conflicts, and lack of security. Positive ecology impacts involve infrastructure and urban evolution, attractiveness, transportation and dark-green technologies concepts. Negative environmental impacts would more often than not refer to traffic problems, infrastructure and the destruction of the natural environment.

Farther, event host destinations were researched in 60 papers, not-host destinations only in ane (i.east., [37]), and both host and not-host destinations in one (i.eastward., [69]). The other 15 literature review papers do not vest to either category (with information in these studies coming from existing literature).

iii.2. Results of the Stage 2

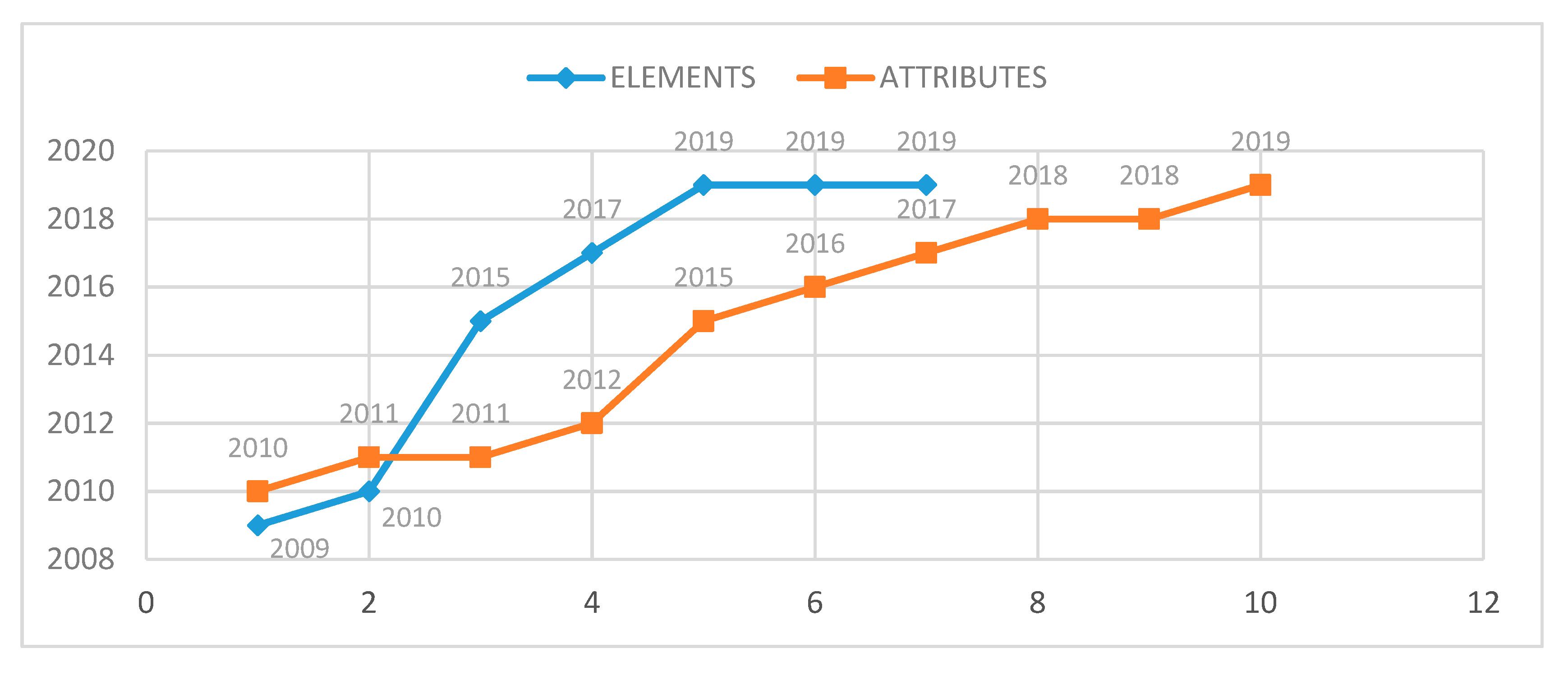

In add-on to the perceptions of residents of the host and non-host communities about the event impacts, this paper focuses on the strategic planning elements and attributes necessary for planning and organizing sustainable sporting events. There are 17 publications originating from this research that refer to strategic event and/or destination elements and strategic event and/or destination attributes. Effigy 2 shows publications between 2009 and 2019, and indicates that enquiry on both planning elements and attributes is a production of the last decade.

Tabular array 5 displays the results of the 7 analyzed papers that refer to event and destination strategic and planning elements, while Tabular array 6 presents the results of the ten analyzed papers that refer to event and destination strategic and planning attributes.

The findings on researched strategic planning elements and attributes are multiple and are therefore matched and systematized based on viii dimensions, namely social, cultural, organizational, logistic, advice, economic, tourism, ecology factors (Tabular array 7). The displayed dimensions are products of event and destination elements and attributes, systematized post-obit previous research and analyzed manufactures.

4. Discussion and Research Directions

Confirming the fact that inquiry conducted on this discipline relates to the more recent past, simply a few research publications on impacts appear between 2002 and 2011, with virtually papers published 2012 to present. When taking into account the strategic planning elements and attributes together, those 2 terms belong primarily to inquiry published in the 2nd decade of the 21st century. While being aware that in that location is surely a number of papers on these topics published in the last century (but not included in the WoSCC database), these results demonstrate the novelty of the subject and mentioned terms in the research expanse, which suggests a lack of literature in the field of sport-tourism and events. It is important to note the increasing popularity of sport-tourism event enquiry, which has high inquiry potential, especially with a focus on economic evolution across different geographical scales—regionally, nationally and globally.

When because upshot host locations, regarding the sample of papers in this written report, Europe (18 publications) and Asia (17 publications) are most represented. If taking North and South America equally one, in that location are 13 publications altogether. Africa (ix publications) and Australia (three publications) saw fewer studies. The reasons why Africa and Commonwealth of australia lag behind in the academic literature is considering these ii continents practice not host large-scale sporting events as often as Europe and Asia, and this tin exist due to the influence of recent mega-event hosting in emerging economy countries such as China and Russia, especially in recent years [87]. It tin be because of the lack of existing and available large-calibration sporting infrastructure on the Africa continent or the altitude of the Australian continent given its geographical remoteness. Planners and organizers seek to improve the security level and prevent disorders and conflicts, choosing secure locations, especially when considering major sport events that require loftier-tech and modern infrastructures, which can exist targets for causing alarm/disorders and even for crime and vandalism [two,38]. In addition, as participants and visitors who attend major sport events come from all over the globe, venues have to exist accessible and it is often preferred that host cities tin be hands reachable from different parts of the globe—so locations which are more distant rarely enter the final bidding stages.

When speaking most the different countries, Due south Africa and South Korea each appear in five publications. Next, a number of papers refer to Mainland china and U.s., as high-economy center locations, merely likewise, and surprisingly, Croatia (four publications). This result for South Africa contradicts previous conclusions about fewer studies focusing on Africa, but the reason why Southward Africa and Croatia were ofttimes studied lies in the fact that these destinations are economically stabile and popular tourist destinations (given the substantial amount of revenue that comes from tourism). Wise [88] added that sport research on Africa primarily focuses on South Africa. While this does not mean that South Africa or Croatia host many events (similar large countries such as United states of america, the UK or China, who do host more large-scale events), when these countries host events, they are intriguing cases for academics to study event or tourism impacts. Other countries, like Brazil and the United kingdom (3 publications), Canada, Greece, Japan, and Portugal (ii publications) were too identified equally popular touristic destinations, and in that sense, are readily equipped with existing infrastructures, accommodations and hospitality-service providers necessary for event organizing and hosting to cater to participants and visitors. In fact, an of import focus is attracting and retaining visitors to capture subsequent visitor spend before, during and after result, and stakeholders who will invest in certain business ventures are crucial for creating economic benefits for any country [16,18]. Synergistic impacts of hosting sporting events and touristic development, such equally increases in tourist figures, seasonality fluctuations, new jobs, increased revenues and tax revenues from expenses were proven in previous studies [17,xx,21,89,90,91]. Additionally, the impacts of sporting tourism volition depend on the achieved level of development, numbers of sport tourists, size of local community, level of evolution and investment in other tourist activities, and if the local customs accepts the hosting of sports tourism and sporting events. If the local community is underdeveloped (similar in the case of Croatia), more products and services will be imported from other local communities or from abroad to provide service to the sport tourist, which would reduce the economical benefits for that place/country [92].

The results on sporting upshot impacts confirmed previous assertions that nigh of the focus was on positive as well as economical impacts. The results evidence that economical impacts mostly include benefits, such every bit new investment in infrastructures, new employment opportunities, increased tourism figures, and new tax revenues [sixteen,17,20,21,89,93]. Some other impacts that is considered a non-monetary effect is destination image enhancement [23,25]. Alternatively, planning for and hosting sporting events results in excessive spending (on the event), increased taxes locally, and higher living costs for local residents [28,29,94] equally investors seek higher render yields. All the same, a new wide economical touch suggests economic sustainability has a positive perception. When compared to other impact types, the number of economic impacts identified in the sample confirms that they are more visible, easier to measure and perceived as more beneficial than other types of impact which are somehow ignored [32,42].

Socio-cultural impacts have get a focus of attention mainly in the concluding few years. This inquiry discusses the importance of not-monetary impacts. Studies take focused on sport participation, quality of life, social cohesion, formation of social capital, pride in place, and new or increased involvement in a foreign country's civilization and visitor attractions (see [33,34,35,36,94,95,96,97]). Each of these points on socio-cultural impacts tin all atomic number 82 to or raise social sustainability. Given the short duration of the project with emphasis on economics impacts and necessities of long-terms policy initiatives, information technology is very important to direct hereafter research to the benefits of socio-cultural impacts on the wellbeing of the community and residents.

Regarding environmental impacts, the results suggest that sporting events produce more than positive than negative environmental impacts. This is opposite to many previous findings that highlight only/mainly negative ecology impacts, or where new sport events are a threat to the host customs's environment. Considerations of threats found by studies include increased traffic bug and air pollution, high quantities of garbage, and college noise levels (run across [28,41,95,98,99]. Enhancing new infrastructure and dedicating urban regeneration/development strategies that focus on territory attractiveness and greenish technologies, resources and transportation are amongst the most ofttimes mentioned positive ecology impacts.

Negative economic and socio-cultural impacts of both small and large sporting events were not a cardinal focus of report, and when assessed, they are always together with positive impacts outlined to a higher place and observed in recent studies [28,29,98,100,101]. A common conclusion is that academics adopt to emphasize positive upshot impacts and that they are not then slap-up to examine negative impacts of whatever type (economic, socio-cultural and ecology). Equally claimed by Getz and Page [2], Giampiccoli, Lee and Nauright [102] and Müller [103], opportunistic and/or political motives frequently lie behind this pattern of behavior, which presents an intriguing upshot for time to come studies.

Furthermore, the fact is that the hos t destination is under the spotlight. The host customs, first of all event organizers as well equally local residents, is ane of the most of import stakeholders of an organized result. Without the support of locals, the arrangement of events will be difficult, specially in case of sport-tourism events which strongly depend on local public institutions, local companies and local volunteers [42]. The same studies mainly examined the attitude of local people apropos how sporting events in the host town will bear upon them and their communities [104,105].

Larger-scale events are not possible without the support of the wider community—that is, the non-host customs. This offers an ambient where the social interaction between the visitors and local population facilitates and develops a positive image of the destination [106,107]. The communities that are not hosts can generate some benefits from sporting events peculiarly for two reasons. Start, the initial finance investment of larger events in non-host destination is minimal, in regards to the host destination. Secondly, the non-host destinations can dedicate themselves to the utilization of all resources because the result organization and management is not express [95]. This research found only ii existing studies that focused on the impacts of sporting events on non-host communities [37,69]. Still, previous studies noted differences in perception between host residents and non-host residents based on the proximity of the town to the upshot [108]. Nevertheless, local residents of non-host towns are usually not questioned about the impacts of sporting event on their town (the so-chosen spill over impact) but about the impacts for the host town [95]. Therefore, the way that residents of places not hosting tin estimate the impacts of sporting outcome on the actual host destination and its residents is still under-researched, and this need considered in time to come work going forward.

When looking at the context of sustainable tourism, outdoor sporting events must be sustainable, taking into business relationship the to a higher place-mentioned affect dimensions on stakeholders. The legacies demand advance planning from the early stages of event design and development. Legacy planning of the consequence and aspects which remain permanent, or which take some determinate period every bit well as human health and well-beingness and education, are factors that can assistance organizational success. Therefore, except for the impacts, specific strategic elements and attributes of sustainable sport-tourism events become very important characteristic when determining sustainability surrounding the organization of outdoor sport-tourism events. In gild to focus on effect elements and attributes, equally the results of this inquiry propose, nosotros place several strategic elements/attributes and grouped them into eight distinctive categories, namely organizational, logistic, social, cultural, economical, tourism, environmental and communication dimensions.

Economic dimensions focus on costs and benefits (every bit suggested past Perić et al. [lxx] and Aicher and Newland [72]), while tourism dimensions refer to new or complementary markets and increasing the number of tourists to events and in destinations. Social dimensions involve the hospitability of local residents, safety and political issues (see Kaplanidou et al. [83] and Mohan [86]) besides as participant preferences. Cultural dimensions relate to local culture, art and celebrated attractions, sport civilisation and cultural development. Environmental dimensions are also important (run across for case [79,85]), and reveal geographical location, natural setting and attractions (especially clean and green environment) and traffic elements/attributes, as each important. All of this was coordinated from the event and destination, for instance organizational and logistical dimensions (elements/attributes such as management, coordination, infrastructure, resource, facilities, entertainment, strategy and monitoring) and the advice dimension (which puts focus on promotion, image, branding, identity and popularity as exposure in mass media). These destination and result strategic elements and attributes are important for designing strategies for planning and evolution of future events (come across for instance [73,75]). In other words, all these dimensions tin guide strategies to assist better understand different stakeholder needs, improve event organization, and leverage upshot legacies. As the 17 publications nearly strategic organizational elements/attributes did not accost the direct human relationship with events impacts, the direction for future research suggests the demand to clarify those relationships: between effect strategy and/or destination elements/attributes (or dimensions) and specific issue impacts.

Indeed, societal needs, shared values and meeting individual group needs, equal rights/access are important points of focus. Every bit suggested past Zhang and Park [6], legacy planning and aspects that concluding, human health and education, policy and principles, monitoring and evaluation processes, and reduced consumption of natural resources are the virtually important factors (from the perspective of the multiple event stakeholders) when considering sustainable evolution and responsible hallmark effect planning and operations. Comparison this written report's results with factors suggested past Zhang and Park [half-dozen], organizational, logistic and communication dimensions can exist considered legacy planning and aspects that last, monitoring and evaluation processes and policy and principles while social and cultural dimensions can be considered as human being health and educational activity. Zhang and Park [6] ended that these dimensions are even more than important for sustainable consequence organizing. Economic and tourism factors are new dimensions necessary for planning and achieving business legacies, better organization, and preventing risk. Special accent is given to the environmental dimension. Global business organisation now suggests the need to focus on outcome impacts aslope biodiversity and the surround, and urban renewal and biodiversity. Therefore, some considerations for upshot planners focusing on environmental impacts include being conscious of any ongoing ecosystem regeneration and dedicated preservation areas, equally these are protected areas and events tin can harm such efforts. These are important to empathize when implementing and preparing for time to come planning and system of sport-tourism events. For this reason, the category named the environmental dimension is proposed. This category matches the reduced consumption of natural resources category that relates to development over time [6]. Those factors, and non only, should be used in planning for future sustainable sporting events. Information technology is crucial to use the findings of previous studies in combination with adept practices equally a base to contribute to the given theoretical framework. In terms of practice, events should have a dedicated cultural program. To achieve this, it is important that the local residents are involved with the issue and participate in the event(s), and (perhaps well-nigh importantly) jobs are created for local residents (and these jobs demand to be sustained, opposed to seasonal or temporary).

5. Limitations and Concluding Remarks

Limitations do exist when conducting systematic quantitative literature reviews. The beginning limitation relates to the defining of the research boundaries for systematic review. This involves transparent inclusion and exclusion of enquiry papers. The central words (i.e., 'sport tourism event' and 'impacts'; 'sport tourism event' and 'legacy'; 'sport' and 'tourism' and 'upshot' and 'chemical element'; 'sport' and 'tourism' and 'event' and 'attribute') in primal fields (from titles, abstracts or keywords) means we have peradventure excluded some articles that were however of relevance (conceptually). This means that some papers that might hash out the idea of 'impact' and 'legacy' but which use different terminology (i.eastward., outcome, outcome, benefit, develop and transform) have been excluded from our sample. This trouble is a common occurrence in literature review papers (run into [61]). In add-on, the criteria for only evaluating academic peer-reviewed periodical articles using WoSCC mean that some influential studies that appear in monographs, volume chapters and postgraduate theses were not a part of this analysis. Moreover, the requirement for articles published in English in this study tin result in limited insight, but this is a common approach with such studies to limit the focus to one publication language or event specific journals [60]. These limitations are largely due to the scope and focus of the research framework agreed when preparing the analysis for this paper, only this does position and frame time to come inquiry opportunities to compare work published in other languages.

To conclude, this paper contributes to the relevant theories of sports management, event management, tourism management and stakeholder management. The systemization and categorization of event impacts from the perspective of key stakeholders and strategic event and destination elements/attributes are necessary for successful and sustainable event system. Moreover, the proposed eight strategic dimensions can also act equally a framework for futurity studies on upshot organization and event impacts. Furthermore, this paper has several applied implications. Foremost, discovering cardinal stakeholder perceptions of impacts and elements/attributes of sustainable outdoor sport-tourism events is useful for organizers of future sport-tourism events to consider. This is of import when trying to get the back up of the entire customs and to gain a better understanding how residents experience both positive and negative event impacts. In addition, past determining the elements and attributes of sport-tourism events, which are crucial for achieving sustainability, this can assistance planners and organizers. If someone perceives one type of bear upon as the about important, in the preparation phase, that individual will so consider relevant elements/attributes of events—this will contribute to the realization of a particular bear on. Indeed, without the inputs from stakeholders, the planning of outdoor sport-tourism events could be much harder. The research results could facilitate organizers and help them to avoid mistakes when planning, organizing, financing and managing future events with a item emphasis on sustainability principles. Knowledge and experience in arrangement of sustainable sport-tourism events is crucial, contributing not but to the sustainable evolution of tourism, but also to the prolonged economic sustainability.

Author Contributions

A.C.T.: paper concept, data collection, and writing of assay and conclusions. M.P.: paper concept and writing of conclusions. N.W.: support for concept and writing of conclusions. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been fully supported by the University of Rijeka nether the project number uniri-drustv-18-103.

Conflicts of Involvement

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the pattern of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of information; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Alexandris, G.; Kaplanidou, Grand. Marketing sport event tourism: Sport tourist behaviors and destination provisions. Sport Mark. Q. 2014, 23, 125–126. [Google Scholar]

- Getz, D.; Page, S.J. Progress and prospects for event tourism research. Bout. Manag. 2016, 52, 593–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shifflet, D.K.; Bhatia, P. Issue tourism market emerging. Hotel Motel Manag. 1999, 32, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Getz, D. Trends, strategies, and issues in sport-event tourism. Sport Mark. Q. 1998, vii, eight–13. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, H.J. Sport Tourism: A Disquisitional Analysis of Inquiry. Sport Manag. Rev. 1998, 1, 45–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Park, 1000. How to develop a sustainable and responsible hallmark sporting consequence? Experiences from tour of Qinghai Lake International Road Cycling Race, using IPA method. Int. J. Tour. Sci. 2015, 15, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peric, M.; Vitezic, Five.; Mekinc, J. Comparison Business Models for Event Sport Tourism: Example Studies in Italian republic and Slovenia. Event Manag. 2019, 23, 379–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, N.; Harris, J. (Eds.) Sport, Events, Tourism and Regeneration; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wise, N.; Harris, J. (Eds.) Events, Places and Societies; Routledge: London, Britain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, Fifty. Triple lesser line reporting every bit a footing for sustainable tourism: Opportunities and challenges. Acta Tturistica 2015, 27, 33–62. [Google Scholar]

- Fedline, Due east. Host and guest relations and sport-tourism. Sport Soc. 2005, viii, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, M.; Zemann, C. Economic, ecological and social impacts of football World cup 2006 for the host cities in Frg. Geogr. Rundsch. 2006, 58, 4–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hritz, Due north.; Ross, C. The Perceived Impacts of Sport Tourism: An Urban Host Community Perspective. J. Sport Manag. 2010, 24, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mules, T.; Dwyer, L. Public Sector Support for Sport Tourism Events: The Role of Price-benefit Analysis. Sport Soc. 2005, 8, 338–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turco, D.1000.; Swart, K.; Bob, U.; Moodley, 5. Socio-economic Impacts of Sport Tourism in the Durban Unicity, Due south Africa. J. Sport Tour. 2003, 8, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalip, L. From legacy to leverage. In Leveraging Legacies from Sports Mega-Events: Concepts and Cases; Grix, J., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2014; pp. 2–12. [Google Scholar]

- Duglio, S.; Beltramo, R. Estimating the Economic Impacts of a Small-Scale Sport Tourism Event: The Case of the Italo-Swiss Mountain Trail CollonTrek. Sustainability 2017, ix, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairley, Southward.; Lovegrove, H.; Brown, Chiliad. Leveraging events to ensure enduring benefits: The legacy strategy of the 2015 AFC Asian Cup. Sport Manag. Rev. 2016, 19, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higham, J.E.; Hinch, T.D. Sport, Infinite, and Time: Effects of the Otago Highlanders Franchise on Tourism. J. Sport Manag. 2003, 17, 235–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na Li, S.; Jago, L. Evaluating economic impacts of major sports events—A meta analysis of the key trends. Curr. Problems Tour. 2013, 16, 591–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnitzer, M.; Schlemmer, P.; Kristiansen, E. Youth multi-sport events in Austria: Tourism strategy or just a coincidence? J. Sport Bout. 2017, 21, 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalip, L.; Green, B.C.; Hill, B. Impacts of sport result media on destination image and intention to visit. J. Sport Manag. 2003, 17, 214–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, Due south.Y.; Mak, J.Y.; Dixon, A.Westward. Elite Active Sport Tourists: Economical Impacts And Perceptions of Destination Image. Effect Manag. 2016, 20, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, S. Sport mega-Events and urban tourism: Exploring the patterns, constraints and prospects of the 2010 World Cup. In Development and Dreams. The Urban Legacy of the 2010 Football game World Cup; Pillay, U., Tomlinson, R., Bass, O., Eds.; Homo Science Enquiry Council Press: Cape Town, South Africa, 2009; pp. 131–152. [Google Scholar]

- Hallmann, K.; Breuer, C. Paradigm Fit between Sport Events and their Hosting Destinations from an Active Sport Tourist Perspective and its Impact on Future Behaviour. J. Sport Tour. 2010, 15, 215–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jago, Fifty.; Chalip, L.; Brown, G.; Mules, T.; Ali, S. Building Events Into Destination Branding: Insights From Experts. Result Manag. 2003, viii, iii–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitson, D.; MacIntosh, D. Condign a Globe-Class City: Hallmark Events and Sport Franchises in the Growth Strategies of Western Canadian Cities. Sociol. Sport J. 1993, 10, 221–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A. A triple bottom line analysis of the impacts of the Hail International Rally in Kingdom of saudi arabia. Manag. Sport Leis. 2017, 22, 276–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, B.Due west.; Shipway, R.; Cleeve, B. Resident Perceptions of Mega-Sporting Events: A Not-Host City Perspective of the 2012 London Olympic Games. J. Sport Tour. 2009, 14, 143–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.; Kearns, A. Path means to a concrete activity legacy: Assessing the regeneration potential of multi-Sport events using a prospective arroyo. Local Econ. 2015, 30, 888–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, N.; Whittam, G. Regeneration, enterprise, sport and tourism. Local Econ. 2015, thirty, 867–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, Fifty. Relevance of triple bottom line reporting to accomplishment of sustainable tourism: A scoping written report. Bout. Rev. Int. 2005, 9, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, H.J.; Walker, Chiliad.; Thapa, B.; Kaplanidou, K.; Geldenhuys, South.; Coetzee, W.J. Psychic income and social capital among host nation residents: A pre–post analysis of the 2010 FIFA World Cup in S Africa. Bout. Manag. 2014, 44, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, North. Sport tourism events as community builders—How social uppercase helps the "locals". J. Conv. Outcome Tour. 2014, 15, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Due south.; Petrick, J.F. Residents' perceptions on impacts of the FIFA 2002 World Cup: The case of Seoul as a host city. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, A.C.; Frawley, S.; Hodgetts, D.; Thomson, A.; Hughes, K. Sport Participation Legacy and the Olympic Games: The Case of Sydney 2000, London 2012, and Rio 2016. Outcome Manag. 2017, 21, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Hautbois, C.; Desbordes, Yard. The expected social impact of the Winter Olympic Games and the attitudes of not-Host residents toward bidding. Int. J. Sports Marker. Spons. 2017, 18, 330–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toohey, K.; Taylor, T. Mega Events, Fear, and Risk: Terrorism at the Olympic Games. J. Sport Manag. 2008, 22, 451–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Hosany, S.; Nunkoo, R.; Alders, T. London residents' support for the 2012 Olympic Games: The mediating effect of overall attitude. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deccio, C.; Baloglu, Southward. Nonhost Customs Resident Reactions to the 2002 Wintertime Olympics: The Spillover Impacts. J. Travel Res. 2002, 41, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesjak, G.; Podovšovnik, A.East.; Uran, Chiliad. The Perceived Social Impacts of the EuroBasket 2013 on Koper Residents. Acad. Tur. 2014, 7, 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Wise, N. Outlining triple bottom line contexts in urban tourism regeneration. Cities 2016, 53, xxx–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timur, South.; Getz, D. Sustainable tourism development: How do destination stakeholders perceive sustainable urban tourism? Sustain. Dev. 2009, 17, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D. Assessing the economic impacts of festivals and events: Inquiry issues. J. Appl. Recruit. Res. 1991, 16, 61–77. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C. Authentication Tourist Events: Impacts, Management and Planning; Belhaven Printing: London, Uk, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Peric, M.; Đurkin, J.; Wise, N. Leveraging Small-Scale Sport Events: Challenges of Organising, Delivering and Managing Sustainable Outcomes in Rural Communities, the Example of Gorski kotar, Croatia. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buning, R.; Gibson, H.J. Exploring the Trajectory of Active-Sport-Event Travel Careers: A Social Worlds Perspective. J. Sport Manag. 2016, thirty, 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D.; McConnell, A. Serious Sport Tourism and Event Travel Careers. J. Sport Manag. 2011, 25, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D.; McConnell, A. Comparing Trail Runners and Mount Bikers: Motivation, Involvement, Portfolios, and Consequence-Tourist Careers. J. Conv. Outcome Tour. 2014, 15, 69–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallmann, K.; Feiler, Due south.; Müller, S.; Breuer, C. The interrelationship between sport activities and the perceived winter sport experience. J. Sport Tour. 2012, 17, 145–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplanidou, Grand.; Vogt, C. The Meaning and Measurement of a Sport Result Feel Among Active Sport Tourists. J. Sport Manag. 2010, 24, 544–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK Sport. Golden Framework. Guidance on UK-Level Back up Available When Bidding for and Staging Major Sporting Events; U.k. Sport, Department for Digital, Civilisation, Media & Sport: London, Britain, 2018.

- Wise, Due north.; Perić, M.; Ðurkin, J. Benchmarking Service Delivery for Sports Tourism and Events: Lessons for Gorski kotar, Croatia from Pokljuka, Slovenia. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 22, 107–128. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, One thousand.M.; Ruiz, C.J.; Sánchez, A.R.P.; López-Sánchez, J.A. A Bibliometric Analysis of Sports Tourism and Sustainability (2002–2019). Sustainability 2020, 12, 2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Edwards, D.; Darcy, S.; Redfern, K. A Tri-Method Approach to a Review of Adventure Tourism Literature: Bibliometric Analysis, Content Analysis, and a Quantitative Systematic Literature Review. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2016, 42, 997–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, C.; Byrne, J. The benefits of publishing systematic quantitative literature reviews for PhD candidates and other early-career researchers. Loftier. Educ. Res. Dev. 2013, 33, 534–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, H.; Hedges, L.; Valentine, J. The Handbook of Inquiry Synthesis and Meta-Assay, 2nd ed.; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield, A. Synthesising the literature as part of a literature review. Nurs. Stand. 2015, 29, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linnenluecke, G.K.; Marrone, M.; Singh, A.K. Conducting systematic literature reviews and bibliometric analyses. Aust. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, E.; Wise, N. An Atlantic split up? Mapping the knowledge domain of European and North American-based sociology of sport, 2008–2018. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwuegbuzie, A.; Frels, R. Seven Steps to a Comprehensive Literature Review: A Multimodal and Cultural Arroyo; eBook; SAGE: M Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, A.; Cuskelly, G.; Toohey, 1000.; Kennelly, 1000.; Burton, P.; Fredline, 50. Sport event legacy: A systematic quantitative review of literature. Sport Manag. Rev. 2019, 22, 295–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittemore, R.; Knafl, K.A. The integrative review: Updated methodology. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 52, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preuss, H. A framework for identifying the legacies of a mega sport event. Leis. Stud. 2015, 34, 643–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richelieu, A. A sport-Oriented place branding strategy for cities, regions and countries. Sport Motorbus. Manag. Int. J. 2018, viii, 354–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, T.C.D.; Miki, A.F.C.; Dos Anjos, F.A. Competitiveness, Economic Legacy and Tourism Impacts: Earth Cup. Revista Investigaciones Turíst. 2019, 17, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubinsky, Y. Analyzing the Roles of Land Image, Nation Branding, and Public Diplomacy through the Evolution of the Modern Olympic Movement. Phys. Cult. Sport Stud. Res. 2019, 84, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D. Event tourism: Definition, evolution, and enquiry. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 403–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadakis, K.; Kaplanidou, K. Legacy perceptions amidst host and not-host Olympic Games residents: A longitudinal study of the 2010 Vancouver Olympic Games. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2012, 12, 243–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peric, Yard.; Vitezic, 5.; Badurina, J. Đurkin Concern models for active outdoor sport event tourism experiences. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersulić, A.; Perić, M. Value network as a key category within issue sport-Tourism concern model: The case of Mercedes-Benz UCI Mount Bike Downhill Lošinj World Loving cup 2018. ToSEE 2019, v, 363–374. [Google Scholar]

- Aicher, T.J.; Newland, B.L. To explore or race? Examining endurance athletes' destination event choices. J. Vacat. Marker. 2017, 24, 340–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peric, Yard.; Wise, Northward.; Dragičević, D. Suggesting a service research agenda in sports tourism: Working experience(s) into business models. Sport Jitney. Manag. Int. J. 2017, vii, 58–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Duysters, G. Enquiry on the Co-Branding and Match-Up of Mega-Sports Event and Host City. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2015, 32, 1098–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziakas, Five. Understanding an upshot portfolio: The uncovering of interrelationships, synergies, and leveraging opportunities. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2010, 2, 144–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersson, R.; Getz, D. Event Experiences in Time and Space: A Written report of Visitors to the 2007 Earth Alpine Ski Championships in Åre, Sweden. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2009, ix, 308–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, M.; Viljoen, A. Destination vs event attributes: Indelible spectators' loyalty. J. Conv. Issue Tour. 2019, 20, 375–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.-South.; Hsu, C.-C.; Huang, C.-H.; Chang, L.-F. Setting Attributes and Revisit Intention as Mediated by Place Attachment. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2018, 46, 1967–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custódio, Thou.J.; Azevedo, A.; Perna, F. Sport events and local communities: A partnership for placemaking. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2018, 11, vi–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, S.O.; Han, J.H. Assessing preferences for mega sports event travel products: A option experimental approach. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, xx, 740–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khor, P.; Radzliyana, R.; Lim, K. Dimension of sports tourists' orientation in the Malaysian context. Hosp. Tour. 2015, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Hashemite kingdom of jordan, J.S.; Funk, D.C. Managing Mass Sport Participation: Adding a Personal Operation Perspective to Remodel Antecedents and Consequences of Participant Sport Event Satisfaction. J. Sport Manag. 2015, 29, 688–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplanidou, K.; Jordan, J.South.; Funk, D.; Ridinger, 50.L. Recurring Sport Events and Destination Prototype Perceptions: Impact on Agile Sport Tourist Behavioral Intentions and Place Attachment. J. Sport Manag. 2012, 26, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrusa, J.; Kim, S.; Lema, J.D. Comparison of Japanese and N American Runners of the Platonic Marathon Contest Destination. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2011, 16, 183–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallmann, K.; Breuer, C. Images of rural destinations hosting small-scale-scale sport events. Int. J. Result Festiv. Manag. 2011, 2, 218–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, L.J. Effect of Destination Image on Attendance at Squad Sporting Events. Bout. Hosp. Res. 2010, 10, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, N. Eventful futures and triple lesser line impacts: BRICS, image regeneration and competitiveness. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2019, 13, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, N. Rugby beyond the Core in Africa. In Rugby in Global Perspective: Playing on the Periphery; Harris, J., Wise, North., Eds.; Routledge: London, United kingdom, 2019; pp. 90–103. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, M.J.; Norman, W.C.; Henry, Thousand.S. Estimating income furnishings of a sport tourism effect. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 180–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higham, J.E. Sport Tourism as an Attraction for Managing Seasonality. Sport Soc. 2005, 8, 238–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solberg, H.A.; Preuss, H. Major Sport Events and Long-Term Tourism Impacts. J. Sport Manag. 2007, 21, 213–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, S.; Ivanova, M. Triple bottom line analysis of potential sport-tourism impacts on local communities—A review. In Proceedings of the Sport-Tourism—Possibilities to Extend the Tourist Season, Varna, Republic of bulgaria, 29–30 September 2011; pp. 168–177. [Google Scholar]

- Fairley, Due south.; Cardillo, M.L.; Filo, K. Engaging Volunteers From Regional Communities: Non-Host Metropolis Resident Perceptions Towards a Mega-Event and the Opportunity to Volunteer. Result Manag. 2016, twenty, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Jun, H.M.; Walker, Chiliad.; Drane, D. Evaluating the perceived social impacts of hosting big-Calibration sport tourism events: Scale development and validation. Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Walker, M. Measuring the social impacts associated with Super Bowl XLIII: Preliminary development of a psychic income scale. Sport Manag. Rev. 2012, 15, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranić, 50.; Petric, L.; Cetinic, L. Host population perceptions of the social impacts of sport tourism events in transition countries. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2012, 3, 236–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peric, Thousand. Estimating the Perceived Socio-Economic Impacts of Hosting Large-Scale Sport Tourism Events. Soc. Sci. 2018, vii, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meurer, R.; Lins, H.N. The effects of the 2014 Earth Cup and the 2016 Olympic Games on Brazilian international travel receipts. Tour. Econ. 2017, 24, 486–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntloko, N.; Swart, K. Sport tourism event impacts on the host community—A case study of Red Balderdash Big Wave Africa. S. Afr. J. Res. Sport Phys. Educ. Recreat. 2008, 30, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantaki, M.; Wickens, East. Residents' Perceptions of Ecology and Security Issues at the 2012 London Olympic Games. J. Sport Tour. 2010, 15, 337–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Ap, J. Residents' Perceptions towards the Impacts of the Beijing 2008 Olympic Games. J. Travel Res. 2008, 48, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampiccoli, A.; Lee, S.; Nauright, J. Destination South Africa: Comparing global sports mega-Events and recurring localised sports events in South Africa for tourism and economic development. Curr. Issues Tour. 2013, xviii, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M. Approaching paradox: Loving and hating mega-Events. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplanidou, K.; Karadakis, K.; Gibson, H.; Thapa, B.; Walker, M.; Geldenhuys, S.; Coetzee, W.J. Quality of Life, Event Impacts, and Mega-Outcome Support among South African Residents before and after the 2010 FIFA Globe Cup. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 631–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.; Smith, B.H. The Impact of A Mega-Event on Host Region Awareness: A Longitudinal Study. J. Travel Res. 1991, 30, 3–x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byon, Thou.K.; Zhang, J.J. Evolution of a scale measuring destination image. Marker. Intell. Plan. 2010, 28, 508–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, M.; Wong, I.A. Value equity in event planning: A case report of Macau. Marking. Intell. Plan. 2010, 28, 403–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovegrove, H.; Fairley, S. Using equity theory to understand non-host city residents' perceptions of a mega-Event. J. Sport Tour. 2016, 21, one–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1. Number of published articles (2000–2019).

Effigy one. Number of published articles (2000–2019).

Figure 2. Number of published articles–event and destination elements/attributes (2000–2019).

Figure 2. Number of published articles–effect and destination elements/attributes (2000–2019).

Table 1. Most frequent sources/journals.

Tabular array i. Most frequent sources/journals.

| Proper name of the Journal | Number of Papers |

|---|---|

| Sustainability | viii |

| Tourism Direction | 7 |

| European Sport Management Quarterly | 6 |

| Journal of Sport Direction | v |

| Sport Management Review | 4 |

| International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics | 3 |

| Current Issues in Tourism | 2 |

| Tourism Management Perspectives | ii |

| Journal of Convention and Upshot Tourism | 2 |

| Leisure Studies | 2 |

| Others | 36 |

| Total | 77 |

Tabular array 2. Dispersion of analyzed papers beyond continents.

Table 2. Dispersion of analyzed papers beyond continents.

| Continent | Number of Papers |

|---|---|

| Europa | 19 |

| Asia | 16 |

| Africa | 9 |

| N America | 8 |

| South America | 5 |

| Australia | 2 |

| Multiple | three |

| Others (no location) | 15 |

| TOTAL | 77 |

Table three. Dispersion of analyzed papers past country.

Table iii. Dispersion of analyzed papers by country.

| Land | Number of Papers |

|---|---|

| S Africa | v |

| Republic of korea | 5 |

| Communist china | 4 |

| Croatia | 4 |

| USA | 4 |

| Brazil | 3 |

| UK | three |

| Canada | two |

| Greece | 2 |

| Japan | two |

| Portugal | 2 |

| Multiple | iv |

| Other countries | 22 |

| Other (no location) | 15 |

| Total | 77 |

Tabular array 4. Impacts and other sport-tourism event dimensions.

Table 4. Impacts and other sport-tourism event dimensions.

| Main Dimensions | Sub Dimensions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Frequency | |||

| Economic | Positive | 81 | Tourism development | 25 |

| Investments and benefits | eighteen | |||

| Destination image | 13 | |||

| Sport development | thirteen | |||

| Business concern opportunities | 6 | |||

| Task increment opportunities | four | |||

| Economical sustainability | 2 | |||

| Negative | twenty | Excessive investments | fourteen | |

| College living costs | 5 | |||

| Lack of strategic planning | 1 | |||

| Socio-cultural | Positive | 37 | Social heritage/uppercase | xiii |

| Educational activity and data | vii | |||

| Socio-cultural exchange | half-dozen | |||

| Pride | 4 | |||

| Increased involvement in sports | three | |||

| Political | 2 | |||

| Psychological | 1 | |||

| Social sustainability | 1 | |||

| Negative | 9 | Disorder and conflicts | 6 | |

| Crime and vandalism | 3 | |||

| Environmental | Positive | 21 | Infrastructure and urban development | 15 |

| Territory attractiveness | four | |||

| Transportation | 2 | |||

| Dark-green technologies and resources | 1 | |||

| Negative | 11 | Traffic problems | 7 | |

| Infrastructure | iii | |||

| Destroy of natural environs | 1 | |||

Table 5. Elements of sport-tourism events constitute in papers.

Table 5. Elements of sport-tourism events establish in papers.

| Author(south) | Event Elements | Destination Elements |

|---|---|---|

| Perić, Vitezić and Đurkin Badurina [seventy] | Resources, Processes, Value Network | Infrastructure, Value Network |

| Kersulić and Perić [71] | Promotion, Grooming, Advice, Coordination | Promotion, Prototype |

| Aicher and Newland [72] | - | Trip Price, Leisure, Group Tours, Location, Shopping |

| Perić, Wise and Dragičević [73] | Participant Interaction, Organizational Processes, Resources, Sport Activity, Sport And Event Services | Surround, Tourism Services |

| Dong and Duysters [74] | Resource, Infrastructure, Facilities, Environment | Economic Development, Promotion Branding, Sport Culture |

| Ziakas [75] | Marketing Efforts, Entertainment, Coordination, Sport And Event Services | Promotion, Nature, Facilities, Tourism Services, Locals Support |

| Pettersson and Getz [76] | Location, Time, Interrelationships | - |

Table six. Attributes of sport-tourism events found in papers.

Table vi. Attributes of sport-tourism events found in papers.

| Author(s) | Event Elements | Destination Elements |

|---|---|---|

| Kruger and Viljoen [77] | Promotion, Support, Economy contribution, Tourists menstruation, Result services | Nature, Tradition, Tourism services, Leisure facilities, Friendliness of locals, Destination accessibility, Community Evolution |

| Su, Hsu, Huang, Chang [78] | Revisit intention | Nature, Facility, Human resource |

| Custodio, Azevedo and Perna [79] | Social bug, Traffic, Cultural development, Leisure | Economic development, Price level, Image, Surroundings |

| Lyu and Han [80] | Transportation, Sport services, Entertainment, Product price | Image, Massive tourism arrivals, Tourism service |

| Khor, Radzliyana and Lim [81] | Financial costs, Result services, Support, Amusement, | Infrastructure, Tourism services, Self-achievement, Escapism, |

| Du, Jordan and Funk [82] | Support, Consequence location, Entertainment, Sport and event services | Paradigm |

| Kaplanidou, Jordan, Funk and Ridinger [83] | Event location, Sport services | Prototype, Tourism services, Safety, Infrastructure and transportation, Shops, Nature, Leisure facilities, Sport facilities, Friendliness of locals, Destination accessibility |

| Agrusa, Kim and Lema [84] | Promotion, Exposure, Sport and consequence services, Resource, Infrastructure, Depression costs | Tourism opportunities and services, Cultural attractions, Shops, Nature, Transportation, Cheap prices, Depression criminal offense and political canter |

| Hallmann and Breuer [85] | Sport and event services, Infrastructure | Paradigm, Politics, Leisure facilities, Culture, Nature, Destination location, Infrastructure |

| Mohan [86] | Sport services | Natural resources, Infrastructure, Friendliness of locals, Politics, Costs, Tourism services, Safety, Leisure facilities, Shops, Culture |

Table 7. Systematized dimensions of outcome and destination strategic elements/attributes.

Tabular array vii. Systematized dimensions of event and destination strategic elements/attributes.

| Dimensions | Strategic Issue Elements/Attributes | Strategic Destination Elements/Attributes |

|---|---|---|

| Cultural | Cultural evolution | Sport culture, Cultural attractions |

| Communication | Promotion, Popularity, Exposure | Promotion, Image, Branding |

| Economic | Prices, Costs, Economic system contribution | Prices, Costs, Economic development |

| Environmental | Location/destination | Nature, Location/destination |

| Logistic | Resources, Infrastructure, Facilities | Infrastructure, Services, Facilities, Traffic |

| Organizational | Coordination, Preparation, Supporters, Entertainment, Services | Management, Organization |

| Social | Interest, Interrelationship, Safety | Hospitability, Support, Rubber, Politics |

| Tourism | New tourist markets, Services | Tourist opportunities, Services |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open up access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC Past) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/four.0/).

Source: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/12/11/4473/htm

0 Response to "The Evolution of Active-sport-event Travel Careers Reviewers Critique"

Post a Comment